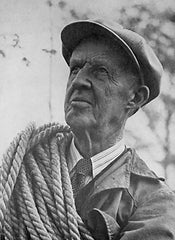

Arthur Cleveland Bent

Posted by Douglas douglas@hummingbirdmarket.com on

Life Histories of North American Cuckoos, Goatsuckers, Hummingbirds

One of our favorites of early published research is the 20 volume series by Arthur Cleveland Bent, The Life Histories of North American Birds. Bent, whose series was first published in 1940 under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution, was one of the country’s outstanding ornithologists and this encyclopedic collection of life histories quickly became one of the classic sources of comprehensive information about the birds of North America. Dover Publications describes this series as “a group of first-hand, concrete observations of specific flocks throughout the continent, describing in readable language and copious detail the nesting habits, plumage, egg form, distribution, food, behavior, field marks, voice, enemies, winter habits, range, courtship procedures, molting, and migratory habits of each one”.

One of our favorites of early published research is the 20 volume series by Arthur Cleveland Bent, The Life Histories of North American Birds. Bent, whose series was first published in 1940 under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution, was one of the country’s outstanding ornithologists and this encyclopedic collection of life histories quickly became one of the classic sources of comprehensive information about the birds of North America. Dover Publications describes this series as “a group of first-hand, concrete observations of specific flocks throughout the continent, describing in readable language and copious detail the nesting habits, plumage, egg form, distribution, food, behavior, field marks, voice, enemies, winter habits, range, courtship procedures, molting, and migratory habits of each one”.

Bent collected the reports of hundreds of birders from throughout North America and from the leading ornithologists and naturalists of the period. We find some of the most interesting reading comes from the descriptive comments of the astute observers of the earlier parts of the 20th century. At that time, field guides and binoculars weren’t the practical equipment birders used. Rifles most easily provided that close-up, bird-in-the-hand view for certain identification. At the time of Bent’s work, Roger Tory Peterson was preparing for publication what would transform the birding world — the first field guide to American birds.

Here is a sample of the types of reporting that one finds throughout the Bent series. Notice the attention to details that most of the writers are careful to include.

While observing the migration of Calliope Hummingbirds in the Huachuca Mountains, Harry S. Swarth wrote:

“After the summer rains the mountains present an exceedingly inviting appearance, particularly so in the higher parts, along the ridges and on various pine covered ‘flats,’ where, with the green grass, a multitude of brilliantly colored wildflowers springs up, often waist high, and in many places in solid banks of bright colors. In such places, in the late summer of 1902, I found the Calliope Hummingbird quite abundant, feeding close to the ground, and when alighting usually choosing a low bush... the first one was shot August 14, and from then up to the time we left the mountains, September 5, they remained abundant in certain localities; none being seen below 9,000 feet.”

Mr. Swarth, in 1904, writes of the appearance of the Rufous Hummingbird in the Huachuca Mountains:

“I have not seen this species at any time in the spring, but about the middle of July they begin to make their appearance; and throughout the month of August I found them very abundant, but frequenting the highest parts of the mountains, principally; more being seen between 8,000 and 9,000 feet than elsewhere. The flowering mescal stalks are a great attraction to them, and they seem to frequent them in preference to anything else. I have seen as many as twenty birds, but with a fair sprinkling of adult males. No adult females were taken at any time.”

Bent himself writes,

“All hummingbirds are fond of bathing, and this species (Broad-tailed Hummingbird) is no exception. On May 15, 1922, while climbing to the summit in the Huachuca Mountains, and following the course of a little mountain stream that flowed swiftly over its stony bed, we stopped to watch a pair of broad-tailed hummingbirds that were bathing in the brook. They chose a spot where the water barely covered a flat stone, settled down in the shallow water, which barely covered their little bodies, and fluttered their wings as they face upstream; after a few seconds in the cold water, they flew off to a nearby branch to shake themselves and preen their plumage.”

“All hummingbirds are fond of bathing, and this species (Broad-tailed Hummingbird) is no exception. On May 15, 1922, while climbing to the summit in the Huachuca Mountains, and following the course of a little mountain stream that flowed swiftly over its stony bed, we stopped to watch a pair of broad-tailed hummingbirds that were bathing in the brook. They chose a spot where the water barely covered a flat stone, settled down in the shallow water, which barely covered their little bodies, and fluttered their wings as they face upstream; after a few seconds in the cold water, they flew off to a nearby branch to shake themselves and preen their plumage.”

Another incident, again from Bent, describes the difficulties of bird identification without the benefit of a field guide:

“While I was collecting birds with Frank Willard in the Huachuca Mountains, he asked me not to shoot any blue-throated hummingbirds, as they were so rare, and I agreed to respect his wishes. One morning we were sitting on a steep hillside watching some large hummingbirds that were chasing each other about in the tops of some tall pine trees on the slope below us. I wanted a Rivoli (Magnificent) very much, so he pointed out one that I could shoot, but, much to his disgust, when we picked it up, it proved to be a male Bluethroat. This illustrates the similarity of the two species in general appearances.”

“Milton S. and Rose Carolyn Ray found a Blue-throated Hummingbird nest in a narrow canyon in the Huachuca Mountains on May 28, 1924. It was “suspended on a wire hanging from one of the rafters’ in a small deserted building”. Mr. Ray says of it:

“The nest is beautifully woven of moss, plant down, and cottony fibers, webbed together on the exterior and decorated there with bits of very bright green moss and pale green lichens. The lining of the nest consists almost entirely of cottony fibers and down. It is unusually large for a hummingbird, measuring 3-1/2 inches high by 2-3/8” across. The cavity is 1-3/4“ across by 1-1/8” deep.”